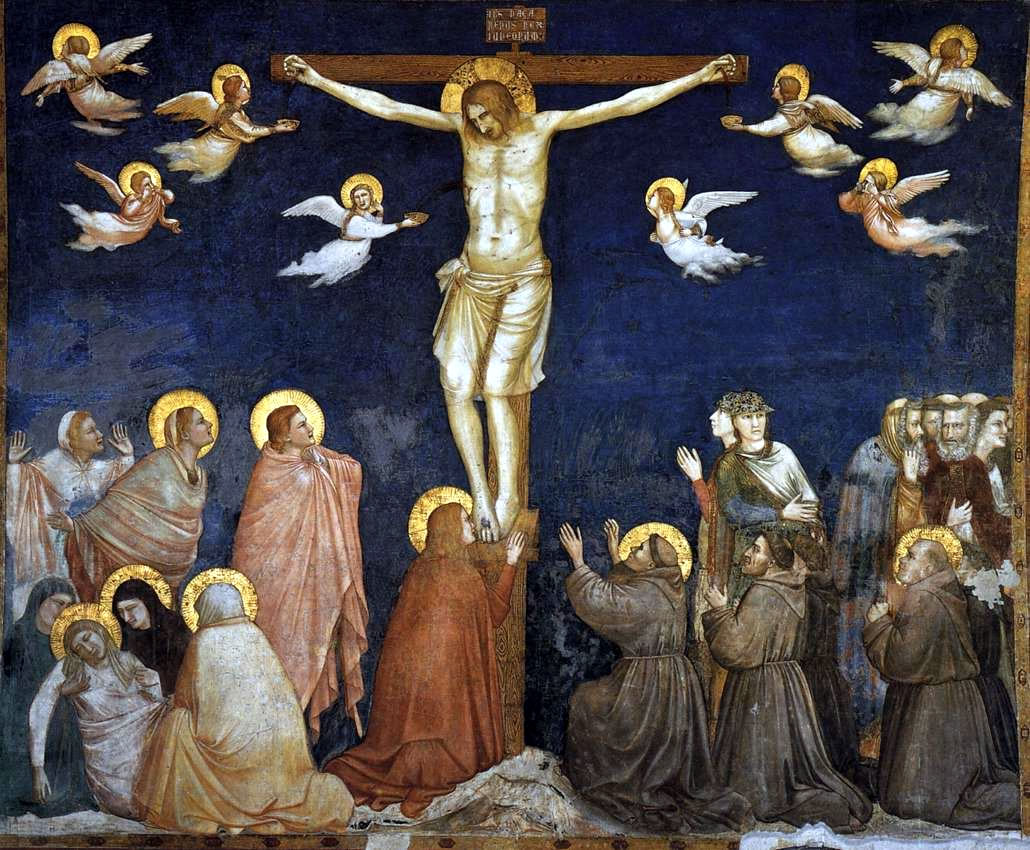

Swoon of the Virgin

- Giotto di Bondone

- Painting

- Circa 14th century

- Lower Church, San Francisco

- Assisi, Italy

- 7099

- Mary , Painting

- Joby Provido

- 10/20/2020

As early as the 12th century, paintings of the crucifixion started to depict Mary fainting as she watched her son hanging from the cross. The British art historian, Nicholas Penny, says that half of surviving paintings in between 1300 and 1500 century show Mary fainting. This idea came from a manuscript entitled, “The Gospel of Nicodemus” (a.k.a. Acts of Pilate) where Mary was described swooning.

The scenes in which Mary is seen to faint are when Jesus leaves her for his final trip to Jerusalem, when he meets her as he carries his cross on the way to Calvary, the crucifixion, and when he is taken down from his cross. These correspond well with a popular book in the 1300s that people were using entitled, “Meditations on the Life of Christ.” Interestingly around the same time, the pilgrimage route of the Via Dolorosa (the route Jesus took as he carried his cross) in Jerusalem had a stop at the Church of St. John the Baptist known as the site of “the virgin’s swoon” or Santa Maria de Spasimo.

Because the swoon of Mary cannot be found in the Gospels, the paintings became controversial around the 16th century and were discouraged by senior churchmen. They argued that a fainting Mary is incompatible with how the Gospels describe her standing beneath the cross.

The controversy was short-lived, and it was probably because the Franciscans were pushing forward the idea that Mary is co-redemptrix (co-redeemer) also around that time. When we review how the Catechism views this role, we can see why the controversy faded away:

"This union of the mother with the Son in the work of salvation is made manifest from the time of Christ’s virginal conception up to his death"; it is made manifest above all at the hour of his Passion: Thus the Blessed Virgin advanced in her pilgrimage of faith, and faithfully persevered in her union with her Son unto the cross. There she stood, in keeping with the divine plan, enduring with her only-begotten Son the intensity of his suffering, joining herself with his sacrifice in her mother’s heart, and lovingly consenting to the immolation of this victim, born of her: to be given, by the same Christ Jesus dying on the cross, as a mother to his disciple, with these words:“Woman, behold your son.”

Lumen Gentium 57-58, CCC § 964

The mystics like Saint Anne Catherine Emmerich tell us that Mary asked God to make her feel whatever her son is feeling. If this is true then it explains the fainting episodes. When Jesus bids her goodbye on his last journey to Jerusalem, his heart must be breaking having to leave his mother in death. Since Christ loved her perfectly, his grief was perfect, and she felt what he was feeling. She felt his broken heart. Again, when she met Christ as he carried the cross along the alleyways of Jerusalem, his heart was crushed once again as he saw his mother’s heart pierced with a sword. She felt his sorrow. But there is no better explanation for her swoon than the crucifixion itself, for when Christ breathed his last and died, she felt that too. It was no swoon; she felt what it was to die. She was dying with her son!

The “swoon” of Our Lady, therefore, should not be seen as a weakness, but as a willing participation in her son’s Passion – all the way to his death. We should see her as co-redemptrix.

Posted by Joby Provido

- Giotto di Bondone

- Painting

- Circa 14th century

- Lower Church, San Francisco

- Assisi, Italy

- 7099

- Mary , Painting

- Joby Provido

- 10/20/2020

Related

- End of Time, Fresco, Scripture

- Christ, Painting, Scripture, Typology, Vatican

- Christ, Mary, Painting, Scripture

- Christ, Mary, Painting, Resurrection, Scripture

- Christ, Dogma, End of Time, Mary, Painting

- Allegory, Christ, Dogma, Mary, Painting, Salvation, Scripture, Typology

- Eucharist, Painting, Typology

- Mary, Movie, Typology

- Apocalypse, Mary, Scripture, Typology

- Apocalypse, Mary, Painting, Typology

- Christ, Mary, Painting, Salvation, Scripture, Typology

- Dogma, Mary

Recent

- 10/13/2023

- 9/28/2022

- 10/20/2020

- 4/18/2020

- 12/9/2019

- 9/6/2019

- 8/25/2019

- 7/2/2019

Popular

- 25,862

- 17,281

- 14,503

- 13,060

Tag Cloud

Did you ever wonder how Mary is the Seat of Wisdom or a Spiritual Vessel?

Mary's titles express how the Church presents her, but some are obscured by language and culture. The book A Sky Full of Stars, explains all her titles in the litany so we get to meet Mary face to face.

Bishop Socrates Villegas says, "A Sky Full of Stars must be an obligatory reference material for religion teachers and seminarians. It helps the reader to see the Virgin Mary within the perspective of sound biblical theology and solid Catholic tradition... [and is] also easy to understand."

Get your copy now either in Hardbound, Paperback, or Kindle