Isenheim Altarpiece

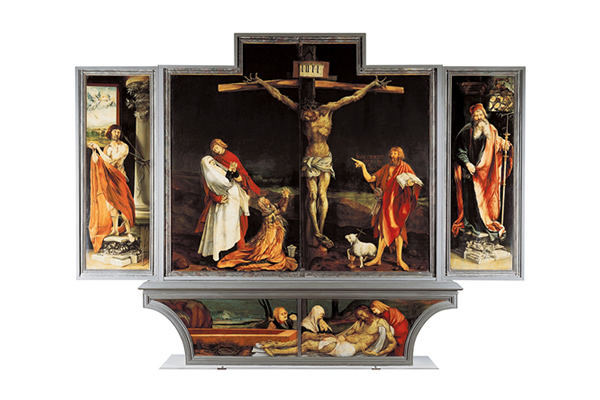

The altarpiece was commissioned by the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, for a backdrop in the hospital chapel – which is how the art piece got its name. It is a polyptych (made of several panels and foldable wings), that are painted, and sculpted. Although the part we are interested to focus on is painted by Matthias Grunewald, we shouldn’t forget that the other genius who sculpted the altarpiece is Niclaus of Haguenau.

First view

Second View

Third View

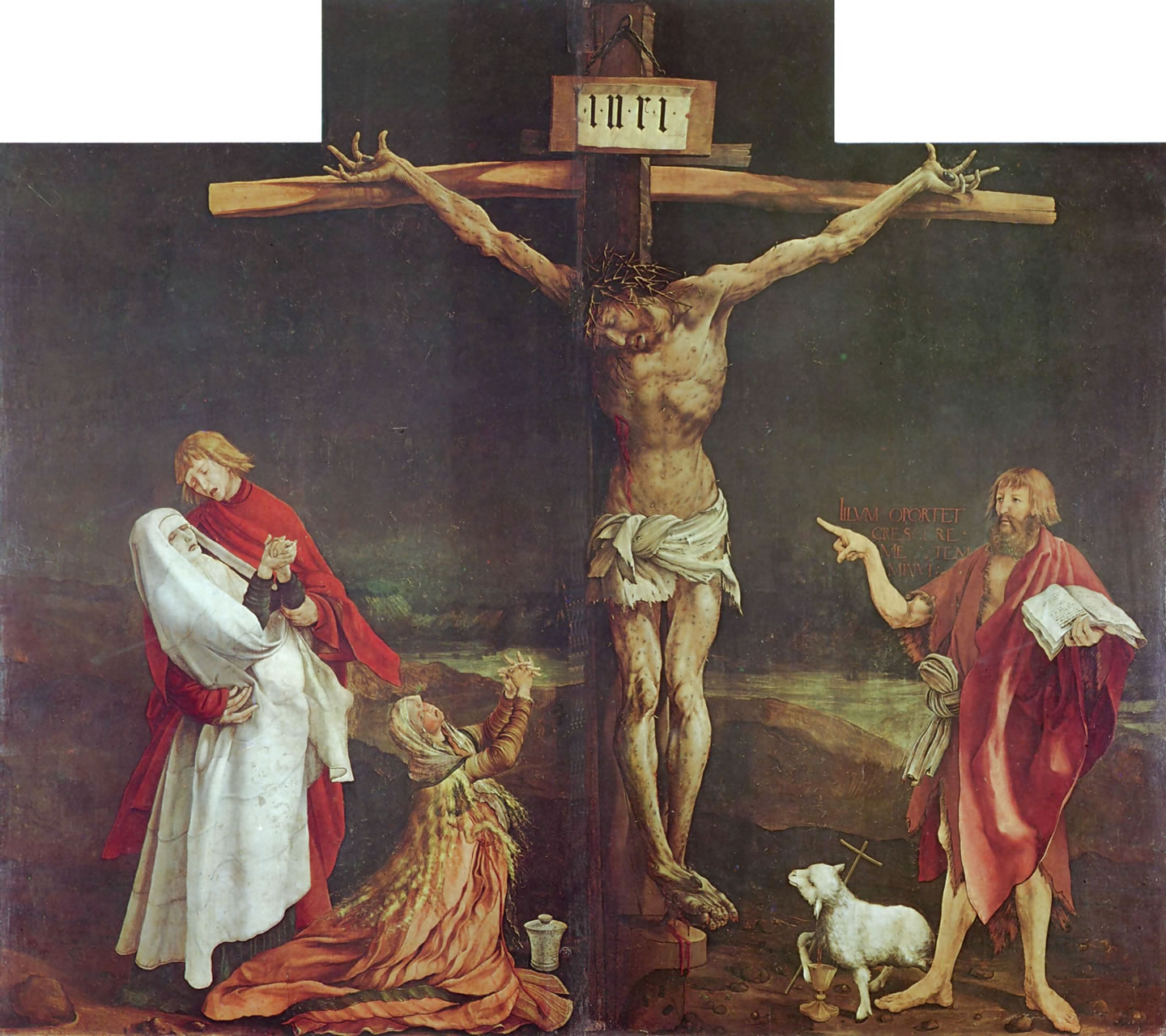

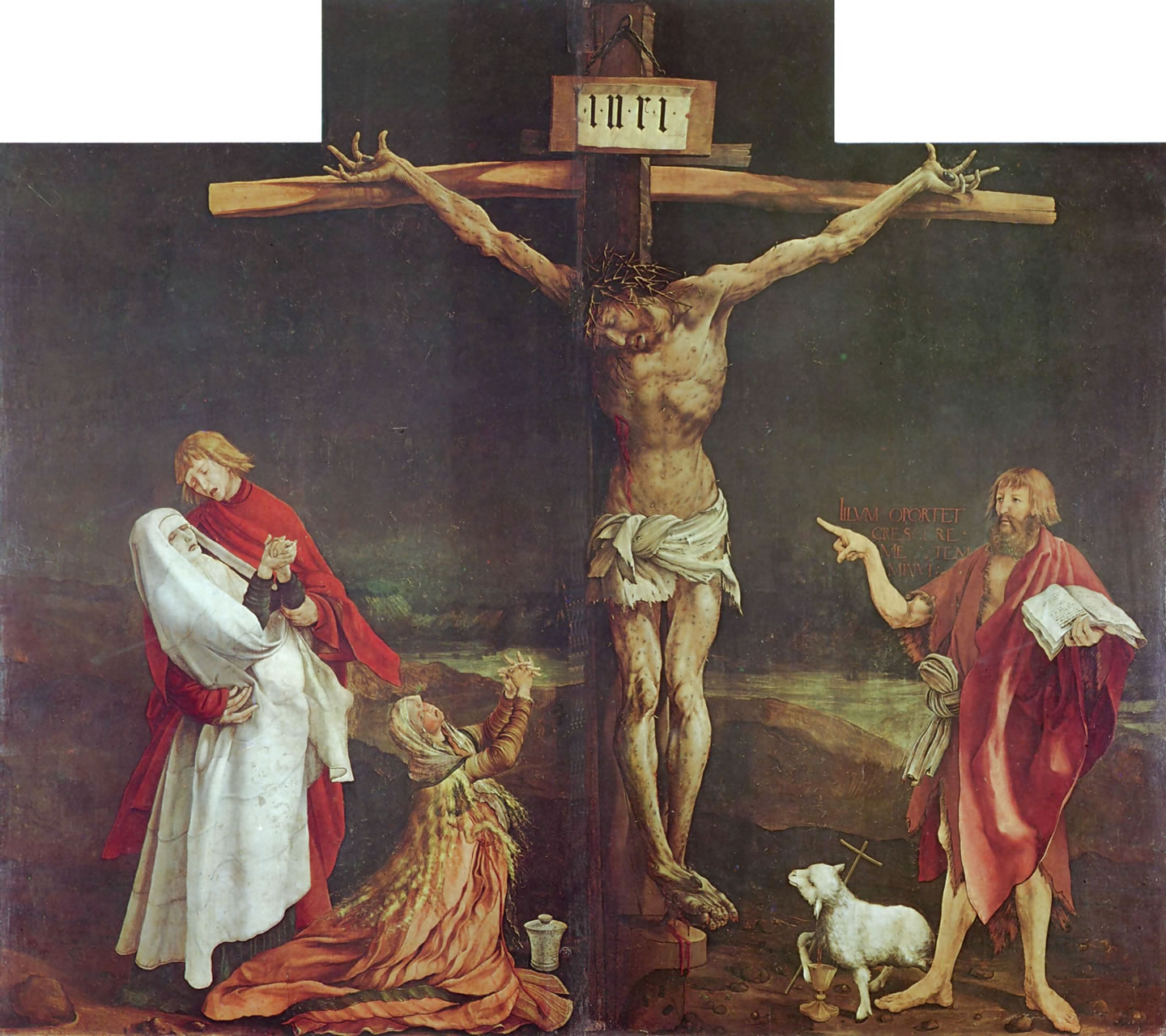

The crucifixion scene shown here is one of religious arts’ most memorable because of the horrific detail in the agony of Christ. We can see his body strained, taut, twisted, and contorted, and his face giving away his anguish. The greenish tinge of his flesh suggests sepsis and necrosis are about to devour him. Mary Magdalene, who is often painted as a lady in red, is below the cross, while the grief-stricken Virgin Mary collapses into the arms of St. John the apostle. Another interesting detail is the darkness that accurately reflects what the synoptic Gospels record that occurred from noon onwards. (Matthew 27:45, Mark 15:33, Luke 23:44)

It can’t be unnoticed that the body of Christ in this painting is full of sores. This is something that Grunewald added to this depiction of the crucifixion for the benefit of the hospital patients. The infirmary was primarily devoted to treating patients with skin diseases. When we see John the Baptist on the right side of the painting, we understand why. The text he quotes is from the Vulgate, John 3:30: “Illum oportet crescere me autem minui.” (He must increase, but I must decrease.) It is a reminder to the viewer that Christ shares their afflictions; that disease is temporary for we all will one day resurrect with Christ having glorious bodies (part of the polyptych is the resurrection.)

The detail we want to focus in between the crucified Christ, and John the Baptist. It is an image of a lamb bearing a flag with a red cross on it, and from whose side blood flows into a chalice. The juxtaposition of the three elements reminds us that Jesus is the lamb of God whose body and blood are present in the Holy Eucharist. This is the backdrop during the mass in the hospital chapel behind the altar when the priest raises the consecrated bread and wine.

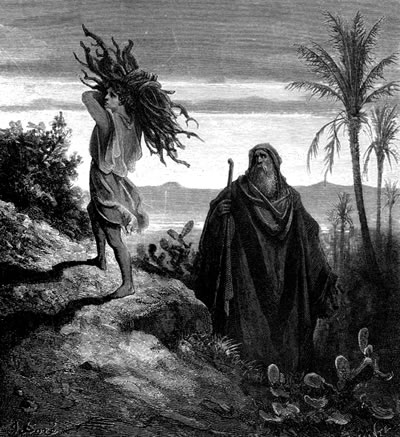

We have to do a little Biblical review to put this together. When God asked Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac they went up Mount Moriah. Isaac was bringing the wood that would be used to burn the sacrifice, but he noticed there was no sacrifice. So he asked, “where is the sheep for the sacrifice?” Abraham answered, “God will provide the sheep…” (Genesis 22:7-8)

We have to do a little Biblical review to put this together. When God asked Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac they went up Mount Moriah. Isaac was bringing the wood that would be used to burn the sacrifice, but he noticed there was no sacrifice. So he asked, “where is the sheep for the sacrifice?” Abraham answered, “God will provide the sheep…” (Genesis 22:7-8)

Fast forward many years later when the Israelites were groaning in their slavery under the Egyptians, God heard them and asked Moses to lead them out. After nine plagues to mock the Egyptian gods, the last plague was to mock Pharaoh himself who was considered a God. In that last plague, God would send an angel to kill every first born. The only way to escape this was to perform the Passover meal. God instructed that each family should sacrifice a lamb (later specified) as an unblemished lamb. The blood should be separated from its body, and the blood smeared on the wooden lintel and doorposts. They should then eat the flesh of the lamb. If they did this, the angel would pass over their house when it was time for the plague. The Israelites did this, but the Egyptians did not, and so Pharaoh found his first born dead the next morning. He was put in his place that he, the “god” of Egypt had no real power of who lived or died. (Exodus 12)

Fast forward again thousands of years when John the Baptist is baptizing in the Jordan. When he sees, Jesus, he says, “Behold, the lamb of God.” (John 1:29) It would have been an odd thing to say unless it was in the Jewish context of the sacrifice of the Passover lamb. So to a Jew, it would have meant, “behold the animal that will be sacrificed.” And that is exactly what Christ is, the Passover Lamb who was sacrificed so that we would be spared from spiritual death, and released from the slavery of sin. It is his blood that was smeared on the wood of the cross, and it is his flesh we eat. He even carries the wood of the cross up a hill as Isaac did.

The little lamb in the painting further expresses the idea that the crucifixion and the Last Supper are connected. (The Gospel of John even alludes to Jesus being sacrificed the same time the Passover lambs were being slaughtered.) During the Last Supper, which has all the trappings of a Passover Seder meal, there is one peculiar item that is missing – the lamb. There is no mention of it whatsoever. But when Jesus takes the bread and tells them that it is his body, and the wine and tells them it is his blood, the imagery could not have been mistaken: he is telling them that his body and blood are separated – just like a slaughtered lamb of the Passover meal. He is indicating that he, in fact, is the Passover lamb.

But there is no real sacrifice because he has not yet been crucified – that would still come on Good Friday. So how can that be? By some mystical means (remember God does not move linearly in time the way we do) the crucifixion is tied up with the Last Supper. The Passover Sacrifice is done inside Jerusalem, whereas Calvary was outside the city walls. So if the two were not connected, scholars suggest, the crucifixion would only be an execution. So during the Last Supper, Christ presented his crucifixion in an unbloody manner through bread and wine. I am sure the apostles must have remembered the Bread of Life Discourse (John 6) when he told them they must eat his flesh. They must have been relieved that this was how Christ was to do it.

We Catholics do the same thing in every mass. Christ said to “do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19) and so we obey his command. One thing about the Passover Meal (and it would be good to read about it or even better, experience it) is that when the Jews commemorate it, the words express their present-ness in the original event. It is as if they are performing the first Passover. This is why the apostles understood that when Christ asked them to “do this”, they and we will also be in that Last Supper where the sacrifice of Calvary is made present. So to us Catholics, the mass is not just a sacred meal or a remembrance. We believe that we are in the midst of a sacrifice. When the priest, wearing sacrificial robes, lifts up the body and blood of Christ to the Father, we are actually made present when Jesus is offering himself on the cross to the Father. It is an opportunity for us to offer ourselves and our work together with a sacrifice we know the Father does not turn away.